It’s time the building that housed Munshi Turab Ali, attached to the court of Bahadur Shah Zafar, is properly maintained and not allowed to just fall into pieces, for it is certainly a reminder of a historic day This is the 162nd year of the Great Revolt of 1857 and tales of it are still heard and published.

In 2007, to commemorate 150 years of the “Mutiny” (as it is erroneously called), Anjuman Taraqqi Urdu(Hind) brought out a calendar with some exquisite photographs and paintings of freedom fighters, starting with a quatrain from Bahadur Shah Zafar: “Lashkar ahad- Elahi aaj sara qatal ho/Gorkha,Gore se ta Gujar nisara qatal ho/ Aaj ka din Id-e-Qurban ka jab hi janenge ham/Aye Zafar ta shekh jab qatil tumhara qatal ho (We will regard this day as the Id of Qurban, Oh Zafar, only when besides the Gorkhas, British, Gujar and others the murderers of the forces of God are also murdered).

Advertisement

This was extracted from Sadiq-al-Akhbar, Delhi, dated 1273 Hijri (1914). The first painting is of the last Mughal emperor in his middle- age, the second of him as an old man with sunken cheeks and a white beard, alongside a photograph of the Red Fort. Then February has Mirza Ghalib and his haveli in Ballimaran, followed by Tipu Sultan and his summer palace.

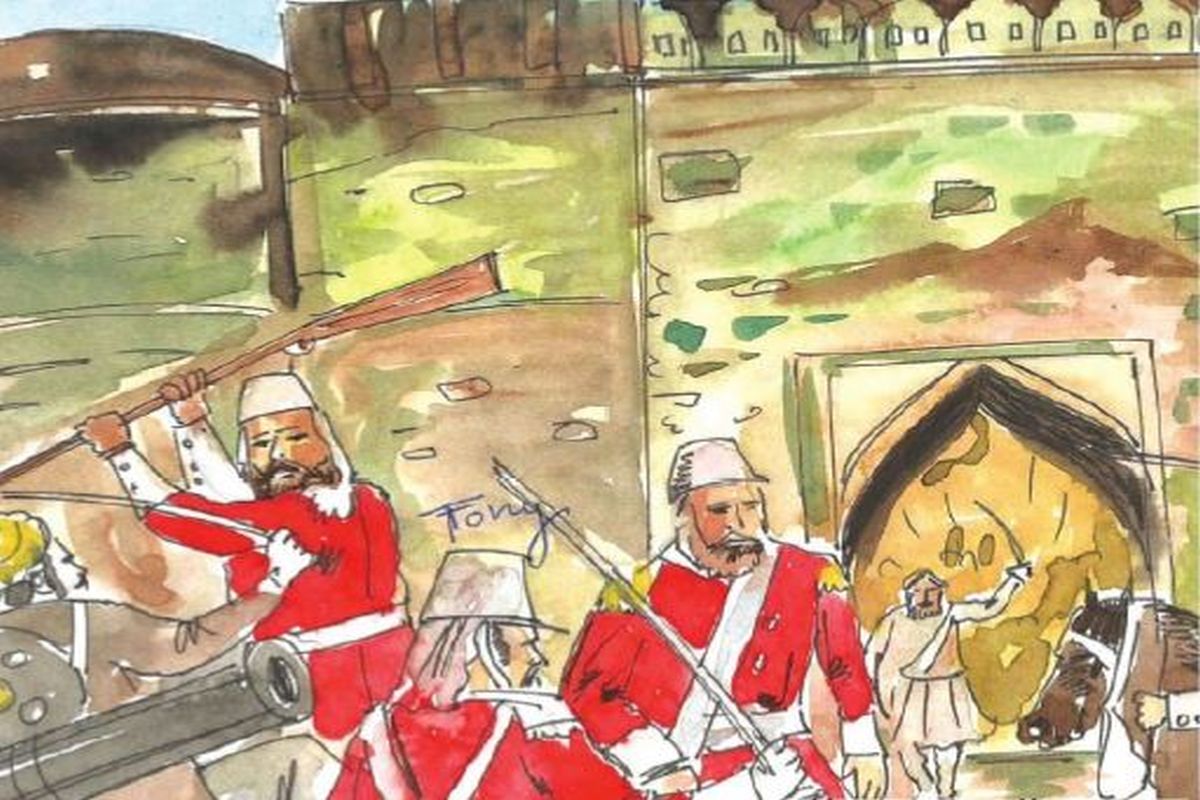

Then the Rani of Jhansi on horseback and her fort; Mangal Pande and Barrackpore Cantt; Tantiya Tope and Gwalior Fort, Wajid Ali Shah and Lucknow’s Kesar Bagh Palace, Maulvi Liaquat Ali and the Allahabad Fort, Hazrat Mahal and the palace named after her, Mir Akbar Ali Khan and the Golconda Fort, Rao Tula Ram and a Mutiny battle scene, Zinat Mahal and the Battle of Delhi.

On the reverse of each month sheet are illustrations like: Traces of the uprising of 1857, a devastated Jama Masjid and the view from it; the Jit Garh memorial; Kashmere Gate after the cannonading by the British; A bird’s-eye view of the old city of Delhi; the throne seat in the Dewane- Am of the Red Fort, blowing up of freedom-fighters; Sunheri Masjid near Delhi Gate; and Bahadur Shah Zafar’s arrest and his grave in Rangoon. All this make the calendar a collector’s item.

In 1950, Ghafoor Mian was 100- years-old and claimed to have witnessed the events of 1857 as a child. The repercussions continued till after the death of Bahadur Shah in 1862. His friend was Mastan Shah, a wealthy aphrodisiac maker, who died at the age of 102 and was reputed to have set fire to the stables of the British cavalry when the “Ghadar” broke out.

A young wrestler of 17 years and four months at that time, he joined the mutinous sepoys in Delhi and accompanied them to Agra, where he eventually settled down some years later. I saw Mastan Shah when I used to visit the old man’s haveli, partly let out to my maternal grandaunt, Mrs Maguire.

At that time Shah Baba was living with his 40-year-old fourth wife (three others, one of whom was older than him, had died). Mastan Shah used to make aphrodisiacs for the rulers of princely States like Awagarh, Bhadawar, Dholpur, Alwar, Rampur and Tonk, among others.

He made a lot of money that way and when he died, his body was carried to the Kabristan on a double bed because he was very hefty, weighing over 250 pounds. He exercised every morning on the terrace, moving about bare-bodied like a latter-day Hercules with long grey locks of hair. Ghafoor Mian lived in Mori Gate, Delhi and had once worked for Mastan Shah, though he could not master the art of making aphrodisiacs like his mentor.

Ghafoor Mian said he and his sister, Sona, used to be hidden by their mother in bundles of grass kept for their domestic cattle, whenever the Angrez soldiers came looking for rebel sepoys in their locality. Kutcha Mir Ashiq in Chawri Bazar is now cluttered up with shops of paper merchants and dingy houses but in the 19th century, it was one of the better localities of Delhi. Mir Ashiq was a nobleman, who enjoyed a position of eminence in the cultural milieu of that time. He was fond of long walks and one who, if accosted on the way, could thrash a ruffian or two.

In the kutcha of Mir Ashiq also lived Munshi Turab Ali, attached to the court of Bahadur Shah Zafar. After the uprising of 1857, when the Jama Masjid was under British control, many petitions were made for handing it back to the Muslim community. The British finally agreed and appointed Munshi Turab Ali as the mutawalli (custodian) of the mosque even though there are some who still question the Munshi’s motives. But jealousy can last for generations.

The house of Munshi Turab Ali still exists in Kutcha Mir Ashiq. When a new roof was being laid on it, the inmates were pleasantly surprised to find several matkas embedded upside down in the ceiling. They served not only to raise the height of the ceiling but also helped to bear its weight for they served as shock absorbers. Matkasor chatties were also used for a similar purpose in the Mughal monuments. Matkasin the ceiling kept the rooms cool in summer. Haji Faiyazuddin and his brothers, who have inherited the house from their great grandfather, have many stories to relate about it. Some of these date back to the “Mutiny” days, when one could stand on the terrace and see the Qutub, Humayun’s Tomb and other monuments as also the sepoys guarding the Kashmere Gate and the Ridge in the distance, where the British were encamped.

The day Delhi was captured by the sepoys there was a big explosion which sent the Munshi’s family hurrying out of the house. It was later learnt that the British had blown up their arms magazine lest it fell into the hands of the freedom fighters.

Then after a few months there was another explosion when the Kashmere Gate was blown up by the attacking British force. The dal being cooked in the house boiled over this time as the inmates rushed out not knowing which way the Firangi troops would make their entry. The house of Munshi Turab Ali is hemmed in by other buildings now and few know that there was a time when the custodian of the Jama Masjid had his office in it. That room, now renovated, is used for entertaining guests with aerated drinks and not the famed sherbets of yore. Long after the British recaptured Delhi, they erected a memorial at the spot where the magazine stood.

In 1962 water seeped into it during the monsoon because of poor maintenance after Independence. The squatters, including some Tibetans, were evicted in course of time, but still, the place became a shelter not only for vagabonds but also for stray dogs and cats. Once a bear that had escaped from a circus near the Red Fort took refuge in it and at another time they found in injured jackal, which had come in from the Kashmere Gate.

In 1962, a night chowkidar discovered a strange scaly animal hiding in the monument. A big crowd collected in the morning and dispersed only when a college girl identified it as a harmless ant-eater or pangolin. There’s a marble slab over the monument praising the bravery of those who blew up the magazine and below it, another one hailing the sepoys, whose rapid advance from Meerut made the British panic. It’s time the building is properly maintained and not allowed to just fall into pieces, for it is certainly a reminder of a historic day when Munshi Turab Ali’s family had to make do with burnt dal. His descendants still talk of it in awe as the explosion of the magazine had sounded like the Crack of Doom, with an old Mullaji shouting that Qayamat had come.

Little did he know that it had come for the East India Company because the “Mutiny” eventually turned out to be its Waterloo.